FLOs will hear these lines, time and time again – “I don’t want to give you the findspot, because the farmer doesn’t want that information out there”

or “because the area is night-hawked all the time and we don’t want to draw attention to it”

First off, let me say that I understand those concerns whole-heartedly! I see why a landowner would not want details of their property online (who would?!) – and I see why responsible detectorists would want to protect their permissions from night-hawkers who don’t care at all about the historical significance of sites. These are concerns that any responsible individual would have, and it’s fine to have them.

However, like many industries who rely on sensitive data in order to run, heritage services must also balance the scales between getting reliable data that can tell us a great deal about a site or an artefact, and protecting landscapes from damage or unwanted attention. We understand that findspots can be a sensitive issue, but we must ensure that the data we collect is accurate, because at the end of the day, it will be the data that stands the test of time and gives our public the information they need to look further into our past, long after we, and our artefacts, have gone.

So, how do we make sure we get good data (findspots), whilst also protecting the area and individuals in question?

Let me show you

I will take you on a step-by-step guide into how the PAS database manages and presents its findspot data for public viewing. I will show you screenshots of what a FLO would see (you lucky things!) alongside what members of the public or people without FLO level or higher access would be able to see.

Our aim is to conserve the findspot data and give enough information to the general public about artefacts that reflect our shared heritage, whilst also making sure that specific areas and sites are protected and location details are general enough not to cause issues for landowners and finders. By default, findspots are displayed as 4 figure national grid references, which covers a huge area (a 1000m square to be exact) and is considered safe when protecting at-risk sites.

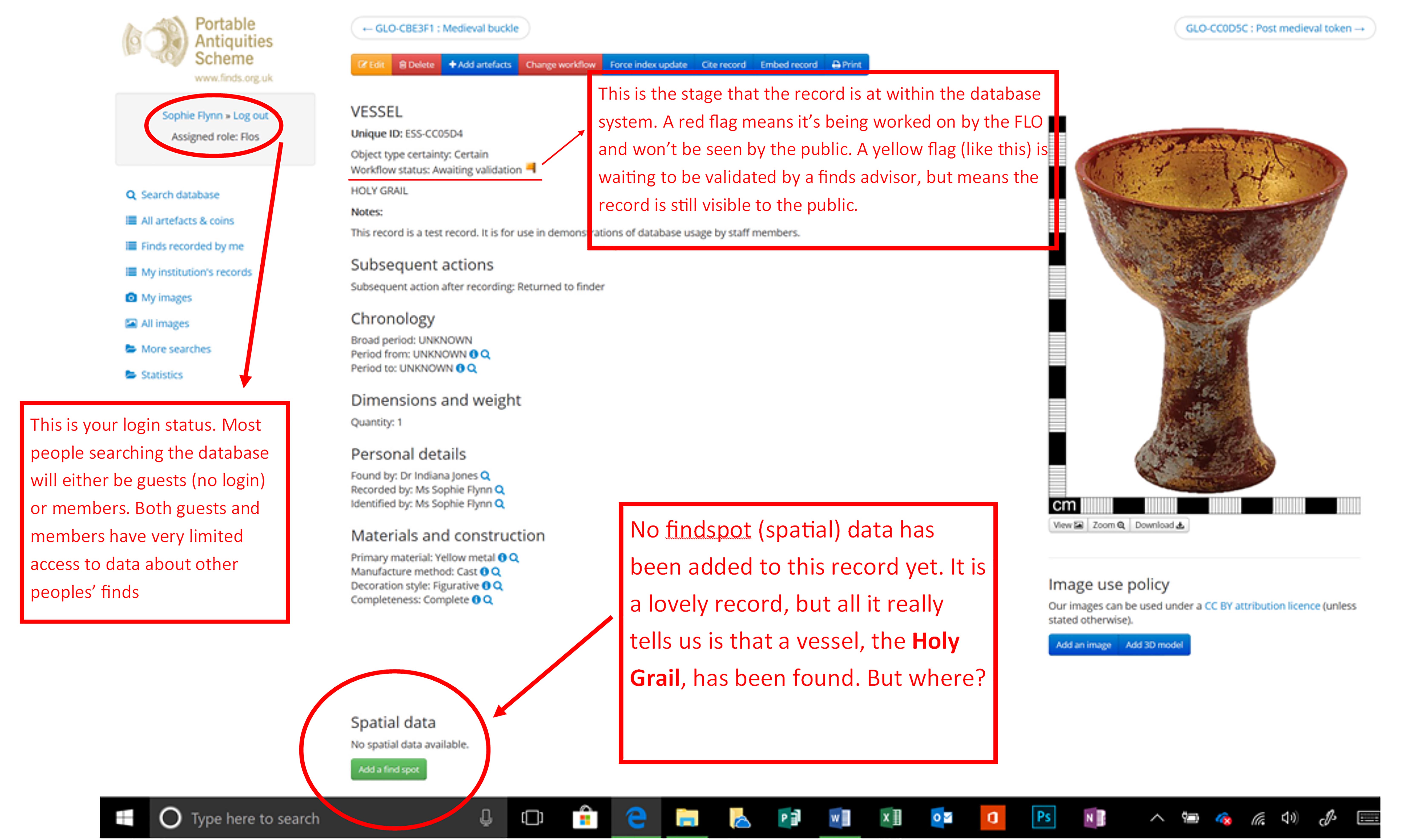

Let’s start with a record as your FLO will see it, as your FLO is the one who adds the findspot information to the records (unless you are a self-recorder).

We want to record the Holy Grail (of course), which has very luckily been found during building works at Colchester Castle (..we wish!). We know where Colchester Castle is because we consulted a map and figured out that the grid reference is TL 998 253. We could also have used digital or online mapping apps to help us find this information, such as Magic by DEFRA (http://magic.defra.gov.uk/MagicMap.aspx) or Where’s the Path (https://wtp2.appspot.com/wheresthepath.htm).

Now let’s look at the screenshots, starting with number 1. You ca n see on the left of the page that the login status (assigned roles) is FLOs. This means that the next few images will show the database as your FLO sees it. Most people who view the database, including finders, will not see this level of information on records unless the find in question is your own, and you have signed up to the database and been listed as the named finder.

1.

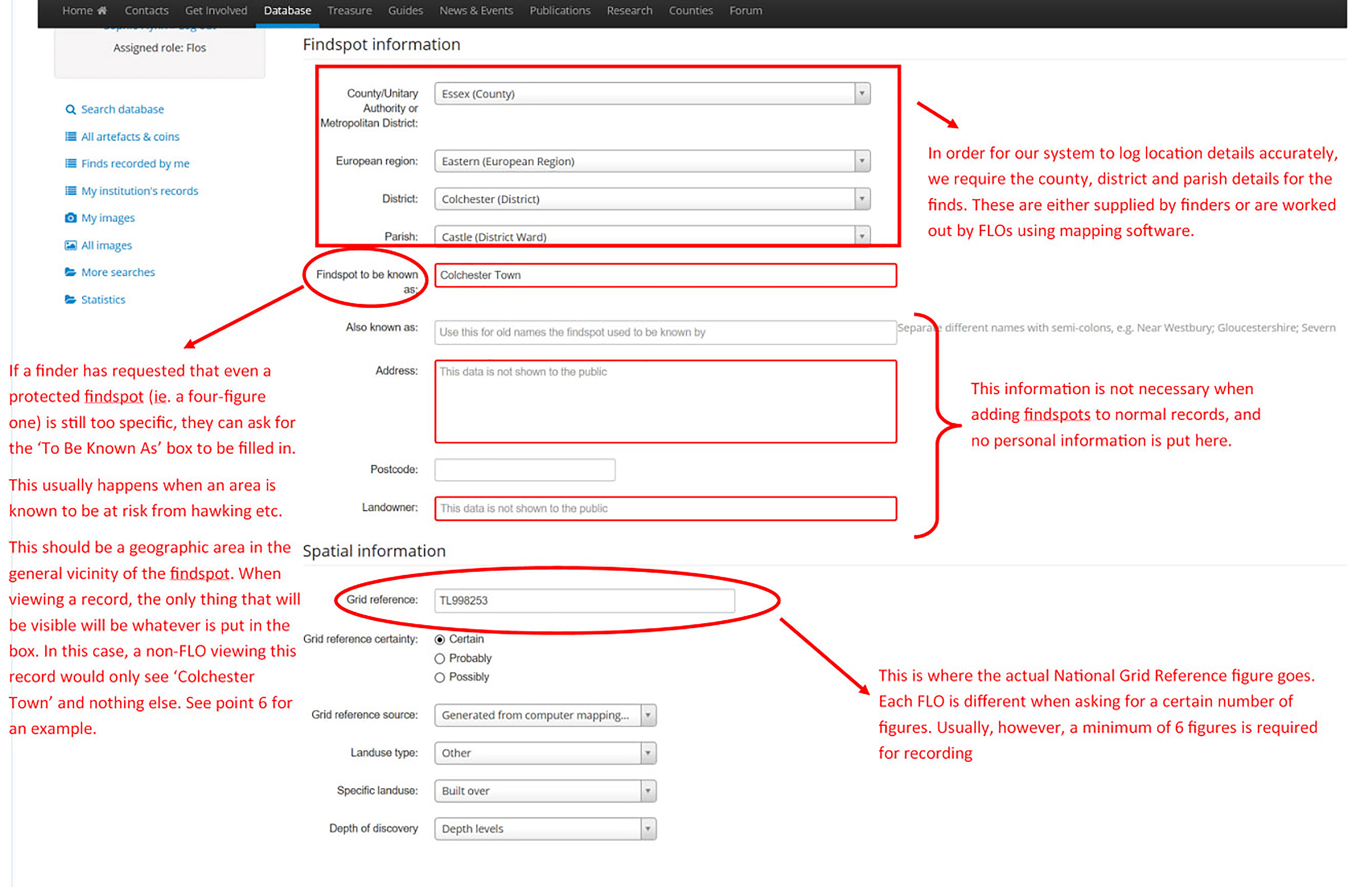

So, let’s add a findspot to this record. We click the ‘Add Findspot’ green button on the bottom of the page, which brings us to the Findspot information page.

2.

We start by filling in the details of which county, district and parish the find is from.

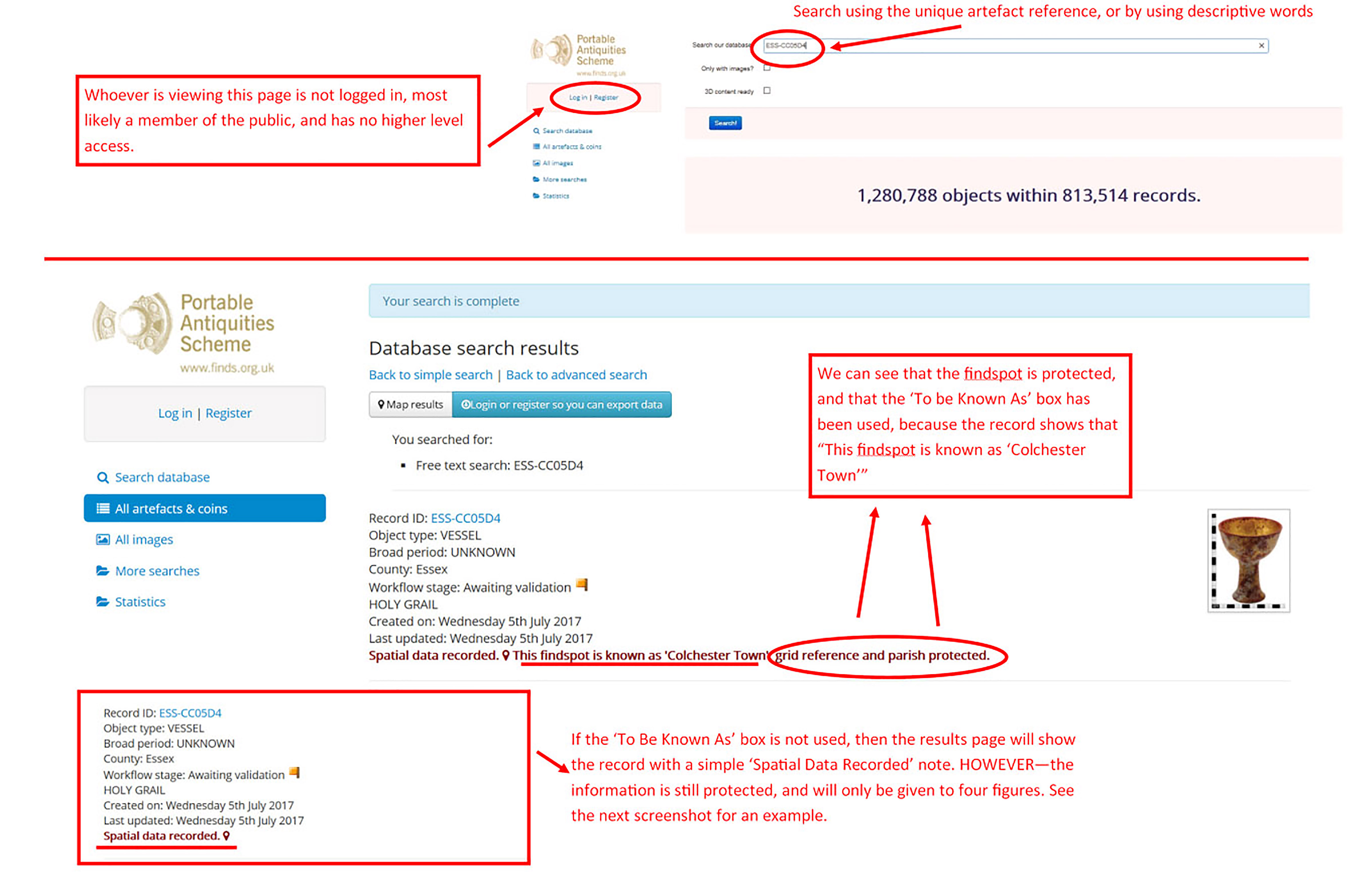

Please note: the ‘To Be Known As’ box should only be used in exceptional circumstances when a site is known to be at risk. The default for all visible findspots is a four figure national grid reference, which is a very large area and certainly enough to protect at-risk sites because of the non-specific location data on display. The usual protected four-figure reference that members and guests will see is usually more than enough to protect a site from unwanted attention. Not using the ‘To Be Known As’ box when it is not necessary will also mean that we get much better spatial information for the general researcher.

We can now move on to how we input the qualifying features of the findspot.

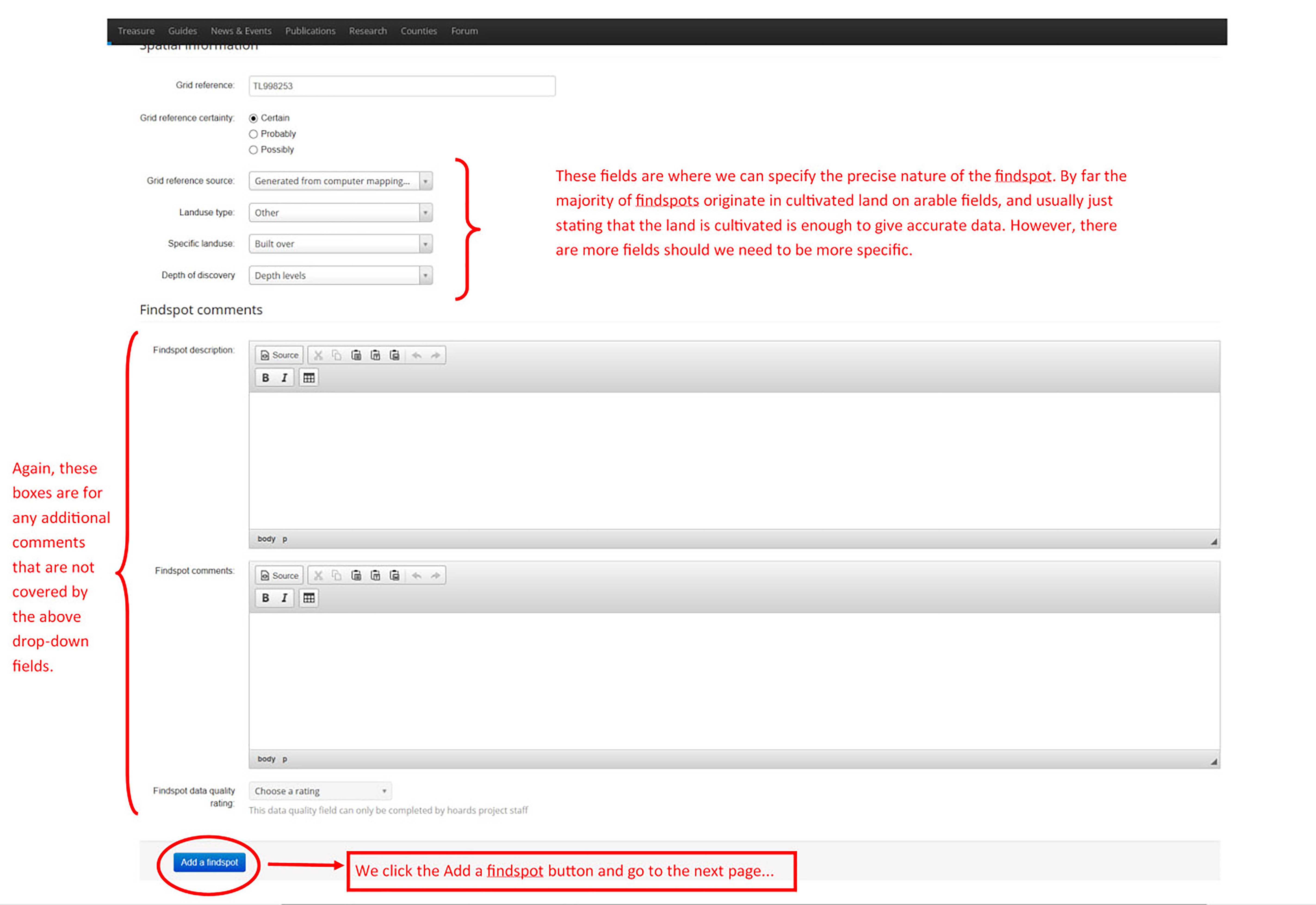

3.

Here we can go into more depth about the nature of the findspot, though this is not always necessary, given that most finds come from arable, ploughed fields, and just saying as much is usually enough in terms of accuracy.

However, in some cases, giving more detail about a findspot is important (for a hoard for instance), and so we have fields where we can do this.

Once we have filled in the findspot details, we can move onto the next page.

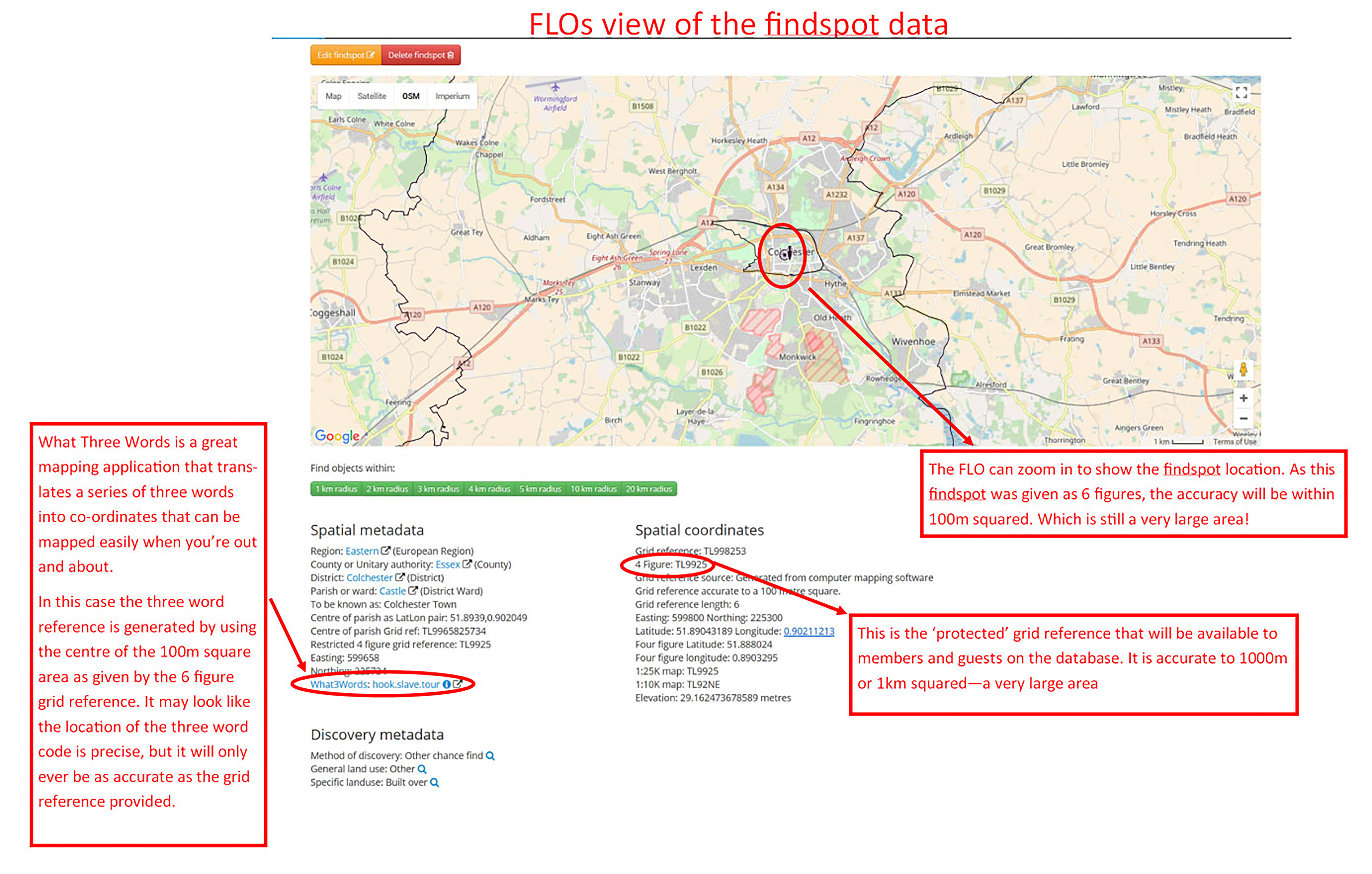

4.

This is what a record will look like with the completed findspot details to a FLO. Remember this – only people with higher level access, like administrators, national advisors and FLOs, will have access to this level of information. All of those people have signed agreements in order to use the database responsibly and professionally as part of their job. For more information on who can see what, please visit: https://training.finds.org.uk/volunteerrecording/guide/accesslevelsexplained

If the find is yours, and you are signed up to the database, your FLO can add you as the finder, and you will get this level of information for your finds only.

Don’t be alarmed!

In this example, seen in point 4, the grid reference provided was TL 998 253 – a 6 figure reference, which you can see under the ‘Spatial Co-ordinates’ heading. If you look under the ‘Spatial Metadata’ heading you will see a ‘centre of parish’ grid reference, which is TL 99658 25734. This is NOT the full 10 figure grid reference for the find. Every parish has a geographic ‘centre’ as mapped by Ordinance Survey, and this is simply the number generated to show which parish the find is in.

Now let’s have a look at how the records and their findspots will appear to the general public – members of the database who view others’ finds, and guests without logins.

5.

This is the search results page, and shows a list of records matching the search criteria. In this case only one record comes up because we searched using its unique record number.

You can see that the first example shows that there has been a record created with findspot information added. The reason the findspot notes are red and highlighted is to reiterate how essential they are for a complete record. Any record without findspot data will stick out because it will say ‘No Spatial Data Recorded’.

6.

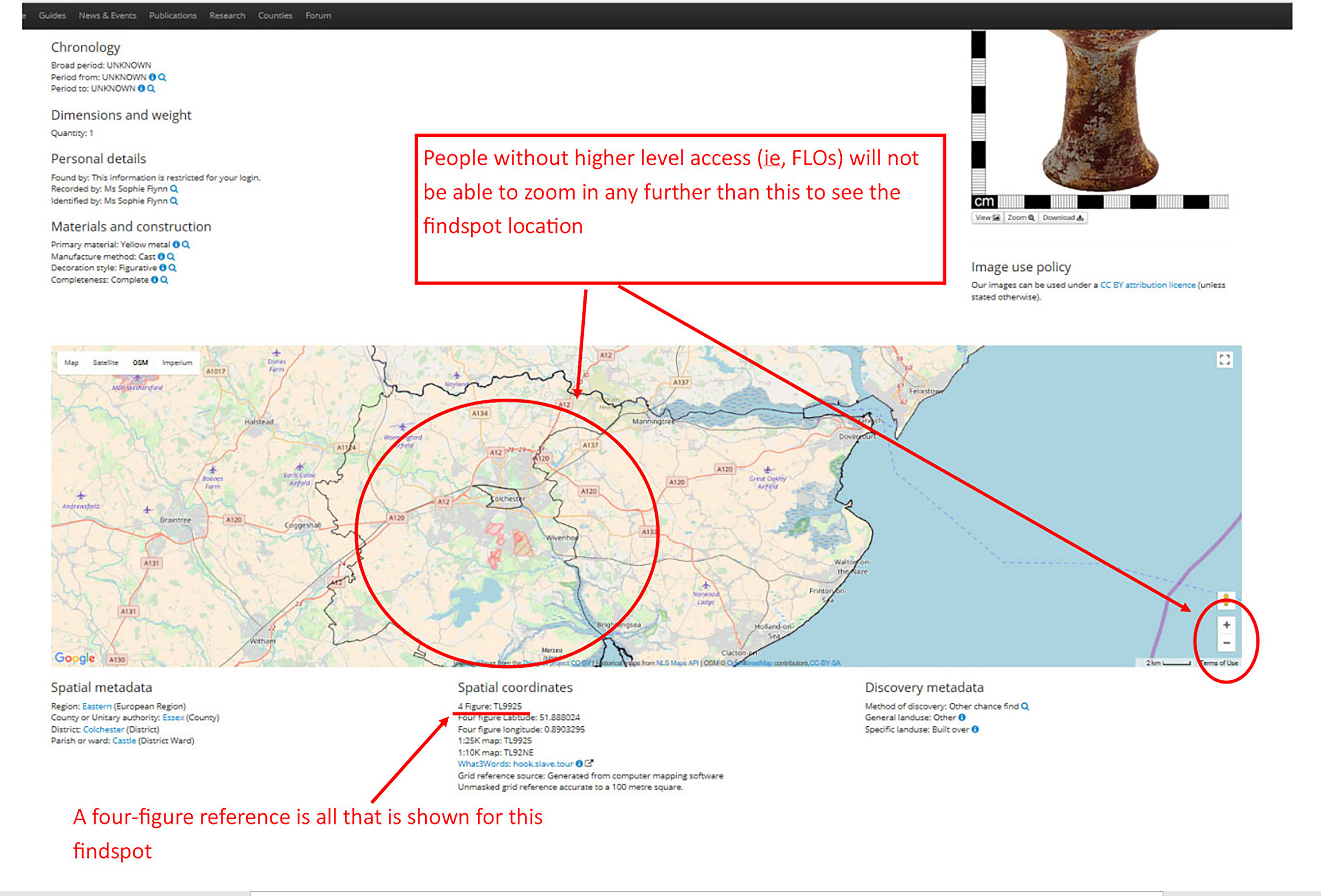

Let’s now look at the findspot info from an actual record, as it would be viewed by a member of the public. In this example, the ‘To Be Known As’ box has not been used, and we can see a map of the general area that the findspot is in, accurate to 1000m or 1km squared. To put this into perspective, the accuracy of this findspot puts it somewhere within the square below:

The map shown on the screenshot below is zoomed in as much as is possible for this level of database access. It is impossible to get any further detail of where the findspot is. We only know the four figure grid reference, the county, the district and the parish.

It is quite clear to see that the general viewer of the database will have no specific information about findspots available to them. The majority of people who view the database do so because they are genuinely interested in learning about the artefacts and their local history. By allowing our shared heritage to be put into a spatial context, we are giving everyone the opportunity to explore archaeology and learn about our history. At the same time, we are protecting that information by heavily restricting access to specific area data, and by ensuring that our database is well managed and secure.

I hope that this walkthrough has been helpful and will put some minds at ease and clear up a few myths about findspots. We do not take findspot data lightly, and understand that it is, quite justifiably, sensitive information. It also happens to be essential information for any reliable record, and we will continue to request that items that we record have findspots. I hope that by working together to understand the concerns from both finders and recorders, we can keep producing top quality records from the wonderful artefacts that are brought in to us.

Thanks 🙂