The biographies of all the objects we record, the way they moved through landscapes in the past via trade, transactions, personal journeys, is fascinating and usually enigmatic. In most cases we know little of the people that owned the objects, how they came to be in the location they are found, and who made them. Some coins or course have the moneyers name stamped on the reverse, but even then the name is usually all we have; occasionally objects may have initials engraved, or a perhaps there is a makers mark…

It is very satisfying then when we can pin-down an artefact, and perhaps its maker, and trace a little more of the story of these archaeological objects. Posy (or ‘posie’, or even ‘reson’) finger rings are a very special class of object. Usually made of precious metal, the rings were exchanged by lovers and are characterised by the inclusion of a short poetic line or phrase on the inner band of the ring, in essence a personal expression of the erstwhile passions of the bestower (Evans 1931, xi-xv). When these rings are reported to us our first task is to establish if they are more than 300 years old, and thus need to be declared as ‘Treasure’ to the coroner. To do this we examine the decoration (if any, many are plain), inscription, and style of the script. Occasionally the interior inscription is preceded by a stamp or ‘makers mark’ that may indicate where and by whom the ring was made. Such was the case with a Posy ring found in fields near Trimdon, Co. Durham, and reported to us in early 2019 (DUR-E8D2A1).

When we examined the simple gold hoop ring we found an inscription on the interior in italic script that read “Love is the bond of peace” with a makers mark at the start of the inscription comprising the letters S and T set within a rectangular frame

Initial research, by one of our very dedicated volunteers Ann, found that the makers mark was used by Durham silversmith and goldsmith Samuel Thompson, listed as working on Elvet Bridge in Durham City between 1751-1785. This immediately made it clear that the ring did not meet the criteria of being a ‘Treasure’ object (being less than 300 years old), and so would be recorded in the same way as all other non-Treasure objects. However, having the makers name with an object is quite unusual so, adhering to part of the Strategic Goals of the PAS “to tell the stories of past peoples and the places where they lived”, we were interested to see if we could find out more about this Durham silversmith. To do so we looked at various sources available (often online) via both the Durham County Record Office (DCRO), the Durham University Special Collections, and various other online genealogical resources and Parish Records. We were able to discover several members of the Thompson family, their Wills and other documentation, and even papers relating to a Consistory Court case in the 1770s which revealed a story that would not be out of place in an Elizabeth Gaskell novel!

John Thompson is likely to have been born in the late 17th century, possibly 1698 as there is a ‘John’ listed in the St. Oswald’s Parish Records (Headlam, 1891) as son of Nicholas Thompson with his trade recorded as ‘whitesmith’. It may be here that we can trace the metal-working tradition in the family, perhaps with a move from ‘whitesmith’ (finishing work on iron and steel such as burnishing or polishing, often synonymous with ‘tinsmith’) to ‘silversmith’ over the next few decades. The records of burials for the Parish in 1737 show a Mary, wife of ‘John Thompson silversmith’, being interred in July of that year; a little further on “John Thompson, silver-smith” is shown as being buried in the churchyard at St Oswald’s in July 1751 (ibid). With this information we were able to trace John Thompson’s will which revealed they had a son, Samuel, who the Parish records show predeceased his father in 1747 (ibid; Durham University DPR/I/1/1751/T3/1-2). The will also revealed that in this event all John Thompson’s “messuages lands tenaments and hereditament” would pass in trust to his grandsons, including another Samuel, and it is this latter Thompson that became the goldsmith who made the posy ring found in Trimdon.

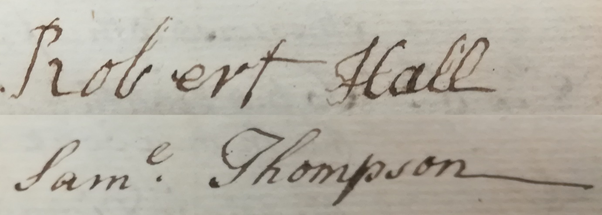

It is the papers relating to the Consistory Court case that really give us insight into the lives of the inhabitants of the “Parish of Saint Oswald’s in the Barony of Elvet” in the later 18th century (Durham University DDR/EJ/CCD/3/1770/21). However, readers hoping for stories of skulduggery and misdeeds may be a little disappointed: the case related to disagreement over who had the right to sit in a particular “stall or pew situate or being in the Parish Church of Saint Oswald…and Diocese of Durham and there thus bounded and described as follows to wit…upon the North Wall of the said Church on the North, and opening into the North Isle of the said Church on the South…”. The documents show that in 1770 Samuel Thompson (goldsmith) cited Robert Hall (Master of Elvet workhouse or poorhouse, trade recorded as both weaver and taylor) for not “having or pretending to have any Right Title or Interest of in or to” the pew. Through the many pages of legal allegations and answers we learn that the Thompson family owned a good deal of land and property in the Parish, including at least “five messuages or Mansion Houses with Shops and Offices” with some “sixty three persons or thereabouts” as tenants and renters. In addition, it appears they already had the right to sit in at least two other large and accommodating private pews within the church. A story develops concerning James and Isable (or Isabel) Watson who, sometime in the early 18th century, built a house or dwelling that seems to be situated on the western side of lower New Elvet

Later becoming insolvent, James is “confined a prisoner in the goal of this county” (and indeed later dies still incarcerated), whilst Isable moves from room to room around the Parish before eventually residing in a “single room”, presumably of the poorhouse, where she too dies in penury in 1769. Her funeral was paid for by her “cousin-german once removed”, our Mr Robert Hall who also, he states, had cared for Isable in her later years. That the Watsons had the right to “the stall or pew situate…upon the North Wall” was not disputed; she had apparently inherited that right from her mother, Mary Dodds. However, Samuel Thompson’s claim related to property his grandfather John had purchased in 1750 for £111 and 16 shillings (approximately £13,000 today, or 3 years wages for a skilled tradesman) that had belonged to Mary Dodds, named in the court documents as a “Mansion House Burgage or Tenement” in Elvet. Thompson’s lawyers argued that the pew, or rather the right to sit therein, had been purchased along with the property. After two years of proceedings and hearings held in the Galilee Chapel of Durham Cathedral, the Consistory Court eventually found in favour of the defendant: “the said Stall or Pew to be Asigned and Confirmed to the said Robert Hall for the use of himself his wife and family to sit kneel pray and hear divine services read and performed”.

As we can see, in the 18th century, as elsewhere in the country, the seating of the congregation and the arrangement of the pews in St. Oswald’s Parish Church was highly contentious, having bearing not only on the spiritual position but also, and perhaps more importantly, in terms of the social position of families in the parish. The organisation of parishioners into pews according to complex hierarchical principles was an unenviable task that often fell to churchwardens, but a task that nonetheless would also have offered a degree of local power and influence. With the socioeconomic flux of the early Post-medieval period, as the industrial revolution gathered pace and Durham began to be transformed from medieval stronghold to economic centre, the church remained at the centre of communal life. Christopher Marsh (2005) has written extensively on this ‘pew’ microcosm of social ordering, viewing it as “an attempt to fix the confusing fluidity of social existence” if only temporarily (ibid, 3). Thinking again of our gold and silversmithing dynasty in Elvet, it is clear from the available records that the Thompsons were a notable local family, and would thus have expected their position in the church to reflect their social position in the community. The will of Samuel Thompson, dated 1773, again reflects the wealth and property held by the family and passed on to his surviving son and daughter (Durham University DPR/I/1/1785/T6/1-2 and DPR/I/2/27 p295), and a ‘Mr Thomson’, possibly Samuel’s son John or grandson (another) Samuel, is recorded next to (and thus owner of) a property on New Elvet on Woods plan of Durham City.

While we cannot know for certain the motivation behind Samuel Thompson’s desire to increase the number of pews held for his family, Marsh’s (ibid, 5) assertion that ”Pews, it seems, were primarily a weapon used by parish elites in their drive to discipline and control the lower orders” is particularly convincing. The lower social status in the community of Robert Hall was highlighted and used by Thompson when he was accused of, and indeed admitted that he “hath no Houses or other Estate in the said Parish of Saint Oswald in his own right as owner and proprietor thereof nor doth he Rent Farm or Occupy any House or Estate…in respect of which he pays or is charged toward the Church or other Parochial assessments of the said Parish”. Yet Hall argued that the work he did in and on behalf of the Parish, caring for and assisting the poor, freed him from any need of payment to the Church; regardless of this fact he had in any case, as he stated, the right to occupy the contentious pew by virtue of inheritance and kinship. It seems the Consistory Court, perhaps embodying the older traditions of the cathedral city, sided with more established forms of social order in the face of the growing challenge from the increasingly wealthy mercantile meritocratic class. Certainly, the cost of the case passed on to the Thompsons, at £10, 10s, 2d (approximately £1000 today, or over 100 days wages), was more affordable for a property-owning goldsmiths family than it would have been for the Hall family.

It would be interesting to know the purchase cost of that simple posy ring, made by Samuel or one of his apprentices in their workshop on Elvet Bridge, to set against the sums recorded in the court case!

Whilst perhaps moving away a little from the pure recording of archaeological artefacts, the above story demonstrates the strengths of the PAS in connecting local people with their heritage and history. In perhaps my proudest publishing moment to date, I was asked to retell this story for the St Oswald’s Parish Magazine, the church where Samuel and robert once sat, and it was very well received by current parishioners (although, I have yet to hear whether it has reignited any long-standing pew disagreements). Key to all we do in the PAS is facilitating the spread of information to local communities, providing data for researchers that would not otherwise have been available, and underpinning research such as that shown above, all instrumental in advancing archaeological knowledge.

References:

Durham University Library, Archives and Special Collections: Consistory Court, Durham Diocesan Records: episcopal jurisdiction and of courts, 1770-1771 promoter: Samuel Thompson of Durham St Oswald, County Durham, silversmith defendant: Robert Hall of Durham St Oswald, County Durham, (DDR/EJ/CCD/3/1770/21)

Durham University Library, Archives and Special Collections: John THOMPSON will, 15 March 1744, Date of probate: 1751. (DPR/I/1/1751/T3/1-2)

Durham University Library, Archives and Special Collections: Samuel THOMPSON will, 4 February 1785 (DPR/I/1/1785/T6/1-2) and registered copy of will, 4 February 1785 (DPR/I/2/27 p295)

Evans, J., 1931. English posies and posy rings: a catalogue. Oxford University Press, H. Milford, London.

Headlam, Rev. A.W., 1891. The parish registers of St. Oswald’s, Durham, containing the baptisms, marriages and burials, from 1538 to 1751. Caldcleugh (printer) Durham

Marsh, C., 2005. Order and Place in England, 1580–1640: The View from the Pew. Journal of British Studies 44, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1086/424947

Ackowledgements

Thanks to Durham County Record Office (DCRO), Michael Richardson, Gilesgate [image] Archive, Durham University Library Archives and Special Collections, and the finder who reported the posy ring.