Iron Age Mirrors

Iron Age mirrors were elaborately-decorated discs of polished bronze with decorative handles, such as the famous Desborough mirror. In 2010, Jody Joy catalogued 58 examples, mainly from southern England. The earliest mirrors from East Yorkshire date from about 400 BCE, but most others are 1st century BCE-1st century CE.

Mirrors are very rare in East Anglia (Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire), home of the Iceni people, although the area has one of the highest recovery rates of Iron Age artefacts nationally. Mirrors are unknown from Norfolk or Cambridgeshire, except for a possible handle from Thetford (NHER: 5853). Three handle fragments have been found in eastern Suffolk: at Akenham (SHER: AKE006), Badingham (SHER: BDG033) and Westerfield (PAS: SF6712). This may reflect the lack of Iron Age burials, the most common location for mirror finds. By contrast, Essex, which is richer in Iron Age burials, has at least ten mirrors. The absence of mirrors in this period suggests that local communities may have been selective about adopting their near neighbours’ artefacts and practices, as well as more exotic imports from Gaul and the Mediterranean, which began to be available through contact with the Roman Empire in the 1st century BCE.

Mirrors have often been described as important status symbols, buried with wealthy women for the afterlife. However, some skeletons have been interpreted as female based on the presence of mirrors in graves, rather than scientific analysis, and many burials were poorly recorded during antiquarian excavations. No mirrors have yet been categorically associated with a male individual, but occasionally have been found in graves that also contained weapons, considered male belongings. Mirrors can also be regarded as marking ‘difference’ rather than status.

Finds relating to personal adornment and grooming practices greatly increase in the Late Iron Age. Mirrors could be part of both private acts of grooming and public performance. Looking at your own reflection in a mirror is a natural response to greater interest in the body. Social norms and ideals were changing and this could have affected relationships between people.

Mirrors may have had uses beyond personal grooming, perhaps used in rituals of divination. A mirror can be used to see behind or beyond the person, even to communicate over large distances. It can catch and reflect light outwards. The surface may also replicate the otherworldly, shimmering boundary of water, relating back to an earlier prehistoric tradition of depositing metalwork in watery places.

Changes over time and space can be seen. These may reflect different groups’ responses during the early contact period with the Roman empire. In East Anglia, as we have seen, they are extremely scarce. Large, intricately-decorated mirrors were abandoned by people in the southeast, yet continued in more westerly parts of Britain. A few Roman mirrors were already in use during the Late Iron Age, suggesting that some people had a range of options. The deliberate choices of material, size, style and decoration perhaps signalled identity, group allegiance or exchange networks.

Roman Mirrors

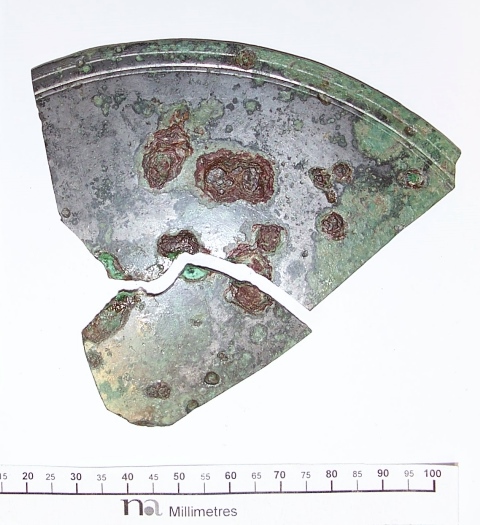

Roman mirrors were small, circular or rectangular, sometimes set within ornamental cases. They often have moulded decoration or punched ring-and-dot patterns around the outer edge of one face. Roman mirrors were made from ‘speculum’: a brittle, highly-tinned copper alloy. This material fragments easily and is often found in small straight-edged chips. Mirrors with handles date to the mid-1st to early 2nd century CE. Like many other forms of material culture, they fade from the archaeological record in the 3rd century CE.

It is thought that all Roman mirrors were imported, suggesting local manufacture ended after the conquest, although some people continued to use and be buried with their Iron Age mirrors. Perhaps imported mirrors were superior in reflectiveness, or were less valuable and more available than the ornate one-off Iron Age types. The two types of mirror may simply have been used in different social situations.

| County | Quantity |

| Cambridgeshire | 3 |

| Norfolk | 104 |

| Suffolk | 49 |

| Total | 156 |

Table: Roman mirror fragments by county.

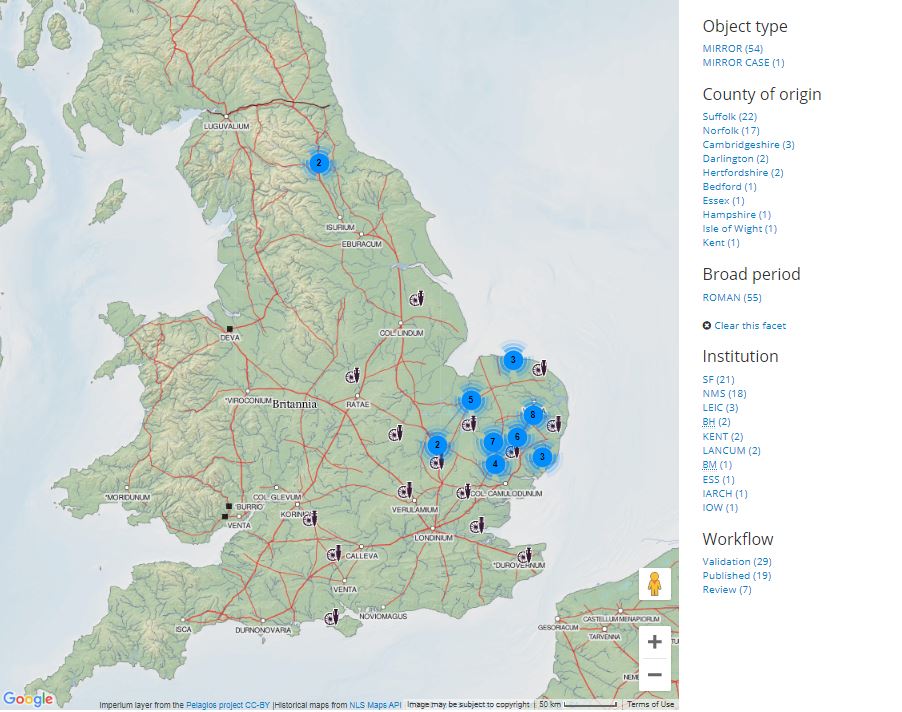

Unlike Iron Age examples, Roman mirrors are widespread in East Anglia. Using data from the PAS and the county Historic Environment Records (HERs), 156 Roman mirror fragments were recorded (original database including HER records closed April 2017, PAS records updated January 2019). Norfolk produced 104 fragments, with clusters from parishes with religious and/or urban centres of the period, including Caistor St Edmund (6), Walsingham (22), Wicklewood (26) and Wighton (5). At the important local capital of Venta Icenorum (modern Caistor St Edmund), a decorated circular mirror was found pre-1894 just outside the walls (Norfolk Museums Service: 1894.76.717, for image see http://www.norfolkmuseumscollections.org/collections/objects/object-3654695206.html/#!/?q=Caistor) and part of a hinged bronze mirror was excavated in 1957 at the nearby temple (NHER: 9787), which may suggest ritual use. Two joining fragments were excavated within the town itself during Donald Atkinson’s investigations in 1929.

In Suffolk, there were finds from the Romano-British small towns at Pakenham (6) and Wixoe (5), along with Scole, on the modern border with Norfolk (6). There were several mirrors recorded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including a ‘speculum’ from Felixstowe (SHER: FEX092) and circular mirrors from Long Melford (SHER: LMD020) and Herringswell (SHER: HGWMISC). Cambridgeshire has very few records of either Iron Age or Roman mirrors, which may be due to historical differences in reporting practices between the counties.

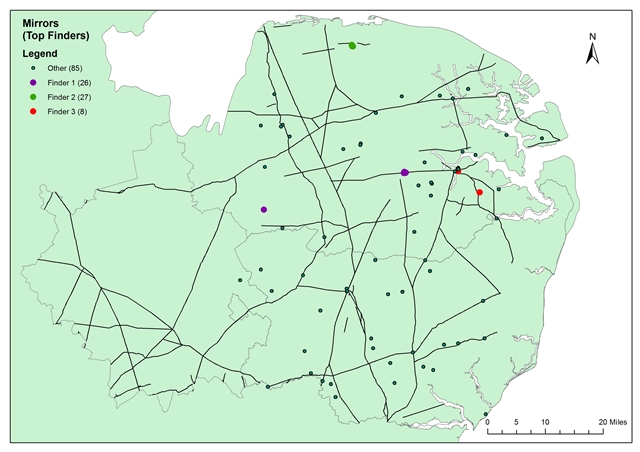

Roman mirror finds on the PAS database are highly concentrated in the Eastern counties. The lack of Iron Age mirrors in the region makes this concentration even more unusual. Recovery bias is an important factor to be considered. During data collection in the Norfolk HER, I noted that a small number of metal-detectorists regularly reported speculum fragments. Plotting mirror fragment findspots confirmed this. The distribution is skewed heavily in favour of three key detectorists. Almost one third of mirror finds reported in Norfolk were made by Finder 1, another third by Finder 2, while Finder 3 found seven pieces all in the same parish. The concentrations reflect their search areas and ability to recognise mirror fragments by their distinctive sharp ‘snapped’ edges and the highly-tinned metal. The Suffolk and Cambridgeshire finds did not show any notable recovery bias.

This demonstrates that the knowledge of individual metal-detectorists has an important effect on the artefacts recovered and reported. Training for other finders (and recorders) would surely increase the known quantities and coverage. This pattern, while unusable for distribution analysis, other than to confirm that people were using Roman-style mirrors in Norfolk, is telling of the processes of recovery for metal-detected finds. It is worth remembering that one mirror can shatter into many fragments, so the numbers of whole mirrors would be considerably smaller. This finding may also have a bearing on excavated and museum finds: mirror fragments are hard to recognise, although once you know what to look for, they are unmistakeable!

Representations on Roman tombstones often show women holding a mirror, with attendants helping them dress or doing their hair. However, two circular cases containing convex mirrors were found in a cremation urn at Coddenham in Suffolk in 1823. On the outside are motifs based on a coin of Nero. One case shows the emperor’s head in profile, and the other an ‘imperial Adlocutio’, an image of the emperor addressing his assembled troops. This ‘male’ and military symbolism indicates that the use of mirrors in the Roman period was not restricted to women. Adlocutio imagery is also found on brooches deposited at the Romano-British shrine at Hockwold-cum-Wilton, suggesting a religious connection.

Stanley Avenue, Norwich

In continuity with Iron Age funerary practices, there are very few early Roman burials in northern East Anglia, although the southwestern area, particularly Cambridgeshire, shows a different tradition had taken hold. Perhaps some local communities were resistant to the practice of burial in the early part of the occupation, while others embraced it. Interestingly, a few early Roman burials do include mirrors.

Two cremation burials from Stanley Avenue, Norwich (NHER: 550) date to around 65-70 CE, a few short years after the turbulent time of the Boudican revolt. In one, the cremated remains of an adult human (interpreted as female) and bones from the right-hand-side of a pig were accompanied by coins of Nero (64-66 CE), a blue glass bead, and a circular copper alloy mirror. The latter had a highly-polished surface, a decorative border and handle, and was found with the remnants of its wooden case. The mirror had been deposited while the bones were still hot from the cremation pyre, and the case, despite being charred, retained traces of Pompeiian red paint.

The second cremation also included adult human and pig bones, and a fragmentary Thistle brooch, dating from the early to mid-1st century CE. With both cremation burials were flagons and platters. Do these materially wealthy burials show us that people in the Iceni territory were adopting the traditions and belongings of their conquerors?

These burials may represent a hybrid ceremony which combined elements of both local Iron Age and imported Roman traditions. The inclusion of the mirror in a cremation burial with pig bones was an Iron Age practice, but the material culture is distinctively Roman and probably imported. In this scenario, the mirror may be understood as an indicator of difference rather than status. This woman and her companion were being marked in death by their community, for despite the introduced materials, there is nothing to suggest that they themselves were not local. The revived practice of burial and the imported objects would have been distinctive, perhaps representing the ‘otherness’ of those individuals, or a way for their community to rationalise the political turbulence of the invasion and rebellion.

Natasha Harlow, University of Nottingham, 2019.

Further Reading

For more information on sites with NHER codes see Norfolk Heritage Explorer http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/, SHER codes see Suffolk Heritage Explorer https://heritage.suffolk.gov.uk/ and PAS object records see https://training.finds.org.uk/database.

Allason-Jones, L. 1989. Women in Roman Britain. London: British Museum Press.

Anon. 1951. Roman Britain in 1950. Journal of Roman Studies 41(1-2): 120-145.

Davies, J. 2011. Closing Thoughts, 103-105 in J. Davies (ed.) The Iron Age in Northern East Anglia. BAR British Series 549. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Davies, J. 2014. The Boudica Code, 27-34 in S. Ashley and A. Marsden (eds.) Landscapes and Artefacts. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Eckardt, H. 2018. Writing and Power in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eckardt, H. and Crummy, N. 2008. Styling the Body in Late Iron Age and Roman Britain. Montagnac: Monique Mergoil.

Gregory, T. 1991. Excavations in Thetford 1980-1982, Fison Way. East Anglian Archaeology 53. Gressenhall: Norfolk Museums Service.

Gurney, D. 1986. Settlement, Religion and Industry on the Fen-edge. East Anglian Archaeology 31. Gressenhall: Norfolk Museums Service.

Gurney, D. 1998. Roman Burials in Norfolk. East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper 4. Gressenhall: Norfolk Museums Service.

Harlow, N. 2018. Belonging and Belongings: Portable Artefacts and Identity in the Civitas of the Iceni. Unpublished PhD thesis: University of Nottingham.

Hutcheson, N. 2004. Later Iron Age Norfolk. BAR British Series 361. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Joy, J. 2007. Reflections on the Iron Age. Unpublished PhD thesis: University of Southampton.

Joy, J. 2009. Reinvigorating Object Biography. World Archaeology 41(4): 540-556.

Joy, J. 2010. Iron Age Mirrors. BAR British Series 518. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Whimster, R. 1979. Burial Practices in Iron Age Britain. Unpublished PhD thesis: Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7999/.

Figures

All maps credited to the author contain OS data © Crown Copyright and Database Right (2017) Ordnance Survey (Digimap/Opendata Licence). Roman road and coastline map layers were kindly provided by Katherine Robbins (adapted from Ancient World Mapping Centre 2012, DARMC Scholarly Data Series 2013, English Heritage, Fenland Survey 1994, and Norfolk Archaeological Trust 2012–6).