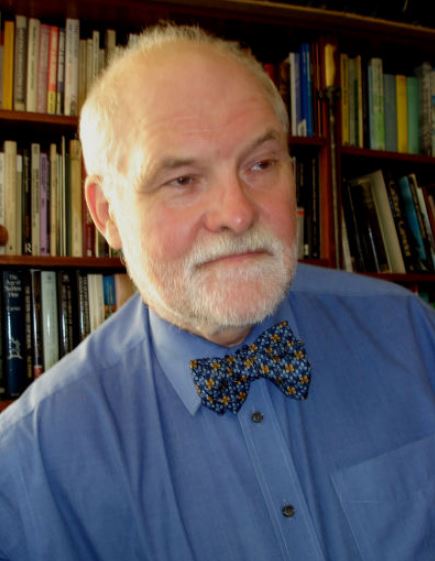

Lucy joined the Portable Antiquities Scheme in 2018 and is based at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter. She also runs finds days in Torquay, Kingsbridge and Plymouth. Here she tells us about her background and why she loves archaeology.

How and why did I get started in archaeology?

I’ve wanted to be an archaeologist from the age of about three or four – I remember being fascinated by a children’s book on the Ice Age and was thrilled to see the excavation of the West Runton mastodon as a child. I was a very geeky teenager and read the Renfrew and Bahn archaeology textbook cover to cover every year during my summer holidays – I couldn’t wait to get to university and finally study the subject. I did a BA, an MA and then a PhD at the University of Southampton and focused on the Etruscans, a group of Iron Age communities from central Italy. This meant regular trips to Rome and working just outside Sienna every summer – a hard life!

What is my greatest achievement in archaeology?

I am incredibly proud of my second book, Lost Civilisations: The Etruscans. It’s a book on the Etruscans for a popular audience and I worked hard to weave in their relevance to our modern society. When I started working on the Etruscans there was very little about them in the popular domain, just nonsense about how mysterious they supposedly were. I’m very proud to have changed that and I wrote this book while on maternity leave with my daughter too – many late nights went into it. I’m also very proud of my involvement with British Women Archaeologists and my work trying to combat sexism and harassment in archaeology.

What period of the past most interests me?

I find the Iron Age fascinating – it’s a period of huge change and whether in Devon or in Tuscany, the same questions apply as people struggle with transformations in the landscape, in the objects they make and use and in how they see themselves. It’s also a period with an image problem, largely thanks to late classical authors. I really enjoy exploring where the Greeks and Romans got it wrong and unpicking why an author might want their readers to see people in a certain way.

Which objects most interest me?

I did my PhD on ceramics, which surprised even me – when I started in archaeology I thought they were incredibly dull and would have been horrified if you’d told me they’d end up being my favourite! I love how clever pots are – how they make you hold and use them in certain ways. And why the decoration works on both your hand and your eye.

Which of the finds I have recorded is my favourite?

I was very happy to record a gorgeous Iron Age dagger pommel in the shape of a human head, which although found in Somerset, came in to me at RAMM in Exeter. I love the face and hair style, the detail and the way the find was executed. But of course, I love the green lumps of copper alloy that used to be Roman coins too. When it comes to coins, if it’s not green I’m not keen!

What is my favourite archaeological object?

The famous Sarcophagus of the Married Couple, from the Etruscan necropolis of Cerveteri, is just absolutely stunning. These two people capture your attention from thousands of years ago effortlessly. If you have the chance to see it in the Villa Giulia Museum in Rome, do go.

What is my favourite historical site or monument?

I’m lucky enough to live where I can see a small Iron Age hillfort, so that’s my favourite. I visit it all through the year, run past the perimeter and love to gaze at it while I do washing up. I love all hillforts though, they all have a really distinct feel to them. I think one of my favourites is Dun Dúchathair on the Aran Islands off the west coast of Ireland. It’s right on the edge of some huge cliffs and is much quieter than the more famous Dun Aengus.

What are my other interests outside archaeology?

Well, I have two small children, so they take up a huge amount of my time – I love hoicking them around to sites but I’m not sure I want them to be archaeologists. In my own time, I love running, especially trail running. There’s a great East Devon based series of 10km and longer races I took part in last year. I’d like to do the Neolithic Marathon (which runs from Avebury in Wiltshire to Stonehenge) if it ever runs again but for now I have the Charmouth Challenge in my sights.

How do I see the future?

I think the future is bright! PAS in Devon has already transformed the way we think about the county. From certain Roman coins not previously found this far west, to evidence of people’s movements and lives in the Early Medieval period, detectorists’ data is making a huge difference locally. I’m looking forward to seeing what everyone discovers.

Five finds from the PAS database and why I like them

DEV-476294 – a Roman brooch found in Bicton, East Devon

A stunning T-shape brooch with glorious enamel work. I’m really interested in these brooches and the regionally specific patterns in their design – South West innovation at work. It dates to AD60-150.

DEV-01DDC5 – a Bronze Age palstave found in East Devon

This gorgeous copper-alloy Middle Bronze Age palstave was found by a lovely lady who had only just started detecting. It’s very special anyway but her enthusiasm and love for it makes it one of my favourites.

DEV-0428C7 – a Roman denarius of Septimus Severus found in Okeford Fitzpaine, North Dorset

This silver denarius of Septimus Severus dating from circa AD196-197 was the first Roman coin I correctly identified. Our National Finds Advisers, Dr. Sam Moorhead and Dr. Andrew Brown, are not only completely delightful but have the patience of saints, teaching me and other PAS staff and volunteers how to identify Roman coins.

DEV-565734 – an Iron Age unit found in Deviock, Cornwall

This silver Iron Age unit from circa AD20-43 was the first Iron Age coin I recorded. The finder put it in my hand and I just thought “Is that what I think it is?”. It was! A truly great find!

DEV-2BAC96 – post-medieval pottery sherds found in Poltimore, East Devon

I thought I’d include something post-medieval for a bit of variety! I really like these Bellarmine jug fragments (AD1550-1700) – they’re a great example of the social history “wrapped up” in a seemingly straightforward object like a jug.