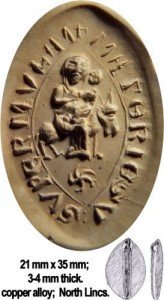

Christmas is just around the corner and it’s time to get those festive decorations up! If you’ve ever wanted your decorations to have an archaeological flavour then we might have just the thing for you. Use the instructions below to create your very own Anglo-Saxon Christmas bauble inspired by the beautiful gold and garnet disc brooches crafted during the early medieval period.

You can use our templates below or design something yourself. There is plenty of inspiration to be found on the database here. Fun for children and early medievalists alike! You can also share your creations with us by tagging @findsorguk on Twitter or Instagram. We’d love to see them!

Instructions

For this activity you will need:

- Scissors and glue

- A hole punch

- Gold card

- Ribbon or string

- Colouring pens or pencils

Step 1: Cut out a circle of gold card to your desired size. A 9cm diameter makes a good sized ornament, but you can go as big or small as you like.

Step 2: Complete your brooch-inspired design! You can colour in one of our templates or, if you are feeling very artistic, you can have a go at drawing your own design.

Step 3: Once you have finished your design, use the glue to stick it onto the front of your gold card circle.

Step 4: You can add some jewels and other finishing touches to really make it sparkle!

Step 5: Once you are happy with your design, use the hole punch to make a hole at the top of your decoration. Thread some brightly coloured ribbon through the hole and tie at the top. Your Anglo-Saxon inspired Christmas decoration is now ready to hang on your tree. Beautiful!

Don’t forget to share your creations with us! Tag @findsorguk on Twitter or Instagram.

![19th century depiction of a Boy Bishop attended by his canons. Unknown Author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://training.finds.org.uk/counties/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Boy-Bishop-Wiki-300x285.jpg)