Welcome to the latest edition of Coin Relief. In this issue Sam Moorhead talks about the base-metal coinage of Domitian. That is, sestertii, dupondii, and asses.

The base-metal coinage of Domitian (AD 72-96). We have previously covered the silver denarii of Domitian’s reign as Caesar (AD 69-81) and as Augustus (AD 81-96). In this piece, I am considering the base metal coinages of sestertii, dupondii, and asses. In broad totals, there are around 1,020 coins on the PAS Database This includes 333 IARCW coins from Wales. These are not included in the first part of the report, but I do consider the Welsh data in the chronological comparison at the end of this article. Without the Welsh coins, there are about 687 pieces (104 sestertii, 136 dupondii, 370 asses and 77 dupondii or asses). A large number of these coins, mostly the better-preserved specimens, have been edited whilst writing this piece, but there is definitely a need for more work on the dataset. However, I do believe that the coins edited do provide a plausible overview of the nature of Domitian’s base metal coinage in Britain. The standard reference for Domitian’s coinage is RIC II, part 1 (2007), the new edition dedicated to the Flavian dynasty.

This discussion of the actual coinage is split into two major elements: a coverage of Domitian’s coinage as a Caesar under Vespasian and Titus (AD 69-81) and then a more lengthy coverage of Domitian’s coinage as Augustus (AD 81-96). These are followed by a chronological analysis of the coins and a consideration of their spatial distribution in Britain.

Domitian as Caesar under Vespasian (AD 69-79) and Titus (AD 79-81)

Coins for Domitian were first struck in AD 72 under Vespasian and continued to be issued under Vespasian and Titus until Domitian became Augustus in AD 81. At present there are 25 asses for Domitian as Caesar; all the clearer pieces date to the reign of Vespasian (AD 69-79) and the vast majority are struck at Lyon in AD 77-8 (RIC 1290). Pieces from Rome are rarer). There are no dupondii and only two sestertii, both for Domitian as Caesar under Titus (AD 79-81). As a general rule, the coins of

Domitian as Caesar generally show a squatter, plumper portrait, in keeping with the general style used for Vespasian and Titus. The portrait becomes taller and narrower after Domitian

becomes Augustus in AD 81.

Domitian as Augustus (AD 81-96)

Excluding the IARCW records from Wales, for Domitian as Augustus (AD 81-96), there there are around 661 coins (102 sestertii, 136 dupondii, 346 asses and 77 dupondii or asses). After a short discussion of the dating of these coins, I will cover the coinage by denomination: asses, dupondii and sestertii. Some asses do not have well-preserved specimens on the PAS Database, but they are cross-referenced with dupondii which share the same reverse. It should be noted that Domitian’s portrait when Augustus becomes taller and narrower than it had been on earlier coins when he was Caesar.

The dating of Domitian’s coins

As for the silver, the base metal coins are normally quite closely dated to specific years, or groups of years. The date of a coin is normally indicated by the consular numeral on the obverse. Domitian held the consulship for the seventh time (COS VII) in AD 81 and was holding it for the seventeenth time (COS XVII) when he was assassinated in AD 96. The consular dates are noted on Tables 1-3, below. It is also worth mentioning the aegis. Nearly

all base metal coins had laureate or radiate heads right. However, in the AD 80s, there was often the addition of an aegis (a breastplate, with the head of the Gorgon Medusa, associated

with Minerva) to the front of the neck. When the date is slightly unclear, the presence or absence of the aegis (as noted in RIC) can sometimes provide a vital clue as to the date of the coin.

Asses

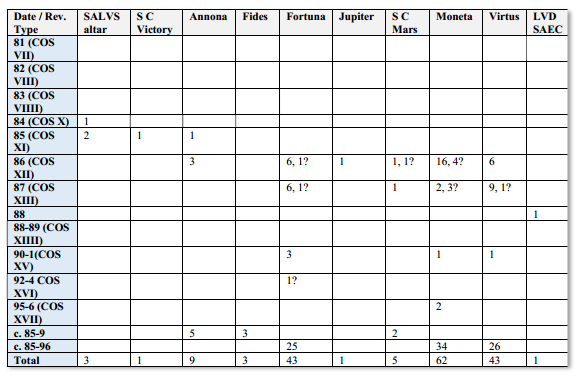

Asses make up the largest number of base metal coins for Domitian with around 346 on the Database. 175 better preserved specimens are tabulated in Table 1. Asses normally have the obverse type of a laureate head right, sometimes with an aegis.

A quick glance at Table 1 shows that the three types struck from AD 85 to 96 are by far the most common:

- FORTVNA AVGVSTI S C

- MONETA AVGVST/IS C

- VIRTVTI AVGVSTI S C

Of these, 63 are dated, 55 of them dating to AD 86 (COS XII) and 87 (COS XIII). Although many of the other types are listed as common in RIC, they are rare as site-finds in Britain – SALVS AVGVSTI S C Altar (3), S C Victory (1), ANNONA AVG S C (9), FIDEI

PVBLICAE S C (3; cf. dupondius), IOVI CONSERVAT AVG S C (1) and

S C Mars (5). There is one example of a coin struck to commemorate the Secular Games in AD 88 – COS XIIII LVD SAEC FEC S C. It is interesting to note that after the large influx of coins in AD 86-7 (making up 79% of the dated coins), there is only

one as for AD 88-9 on the PAS Database.

Dupondii

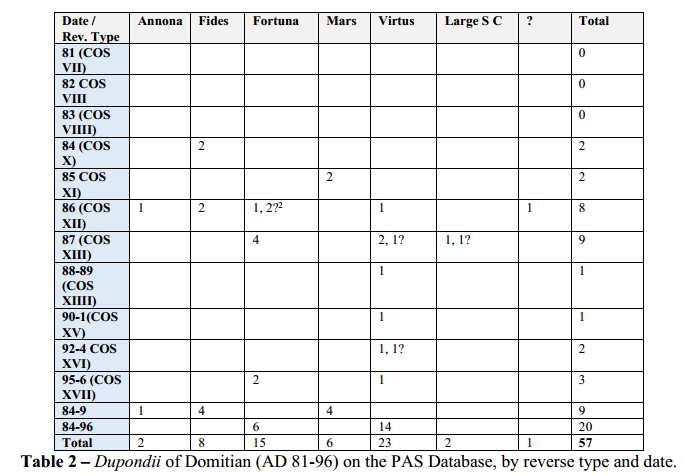

There are far fewer dupondii on the PAS Database with 136 specimens, of which 57 better preserved pieces are presented in Table 2. The obverse type is normally a radiate head right, sometimes with an aegis.

The two reverse types struck from AD 84 to 96 are again the most common:

- FORTVNA AVGVSTI S C (15 pieces)

- VIRTVTI AVGVSTI S C (23)

FIDEI PPVBLICAE S C (8) and S C Mars (6) are reasonably represented but the ANNONA AVG S C and IMP XIIII COS XIII CENSOR PERPETVVS P P around large S C are much rarer with only two recorded specimens for each. Again, coins of AD 86 and 87 are the most numerous, but with dupondii only represent 61% of the dated coins (as opposed to 79% for asses).

Sestertii

There are 102 sestertii, but many are in very poor condition and this report only includes 34 of the better specimens, as shown in Table 3.

There is one early sestertius, with S C Minerva, dating to AD 81-2; this is the only base metal piece for these two years on the PAS Database. By far the most common type is the IOVI VICTORI S C issue showing Jupiter seated. All the other types are much rarer with only a few specimens each – S C Domitian and Victory (4), S C

Domitian on horseback (1), S C Domitian at altar with soldiers (2), S C Domitian and German captive (2), and S C Domitian and Rhenus (2). This time the number of coins for AD 86-7 only makes up 29% of the dated coins, way below the 79% and 61% for asses and dupondii. Instead, the best represented years are AD 95-6 with 43% of the coins. Below, I argue that this might be because there was a shortfall in silver arriving in Britain in AD 95-6.

A Chronological analysis of Domitian’s base metal coinage

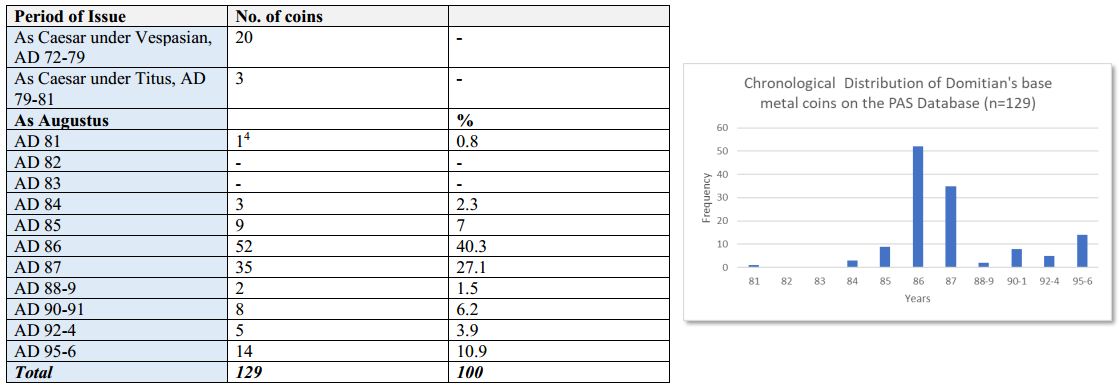

Several studies of the chronological distribution of Domitian’s base metal coinage have been made in the past. It is interesting to see what the PAS Data can contribute to the debate. At the outset it should be stated that the 129 dated specimens in the PAS data, and the 151 dated coins in the Welsh data (discussed below and IARCW records on the PAS Database) are by far the largest samples available for study from Britain.

A quick glance at the figure below shows that there are very few base metal coins arriving in the province for the years 81-4, with a slight rise in AD 85. It is in AD 86 and 87 that the peak of coin supply occurs, coins from these years accounting for 67.4% of total supply for the reign; asses are the dominant denomination in these two years (see Table 1). The drop-off in AD 88-9 is marked and there are only small totals in the period 90-4. However, there is a slight upturn in AD 95-6, caused by the nine IOVI VICTORI S C sestertii recorded on the PAS Database (see Table 3).

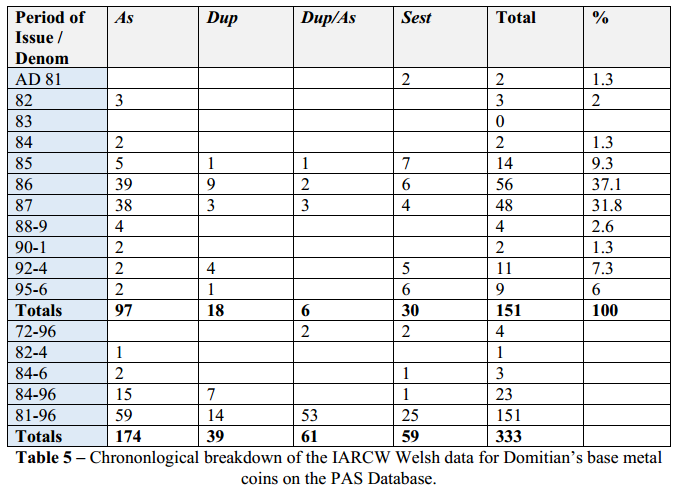

The Welsh (IARCW) Data on the PAS Database

I noted that the 333 coins from Wales (IARCW) were not included in the general discussion of the coinage. Because these coins come from hoards, excavations and detector finds it is difficult to use them alongside other PAS data in analysis. However, for Domitian’s base metal coins they provide an important group of coins which can be used in chronological analysis. There are 151 coins which can be dated precisely, making this a comparable dataset to the 129 pieces recorded as normal PAS finds. Table 5 shows the data in summary form.

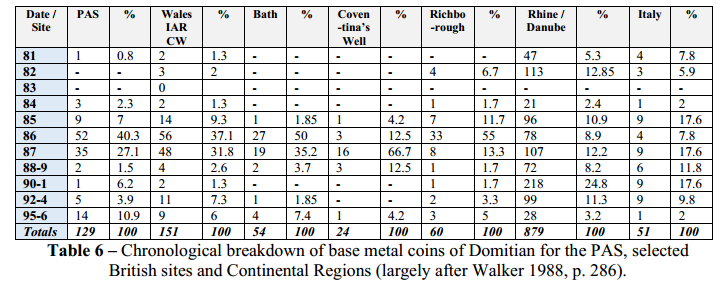

Comparison of PAS and IARCW data with other sites in Roman Britain and regions on the Continent

It is important to compare the PAS and Welsh data with other sites in Britain and regions on the Continent. Because I do not have access the Hobley (1998) and Carradice (1983), I am reliant on statistics provided by David Walker in his Bath report, which does draw in part on the work of Ian Carradice. Table 6 shows the totals for various sites and regions set against the PAS and IARCW Welsh data (after Walker 1988, p. 286). The other three major British assemblages come from the Sacred Spring at Bath (Walker

1988), Coventina’s Well (Hadrian’s Wall), and Richborough (Kent).

The figure below shows how the British groups have quite a similar profile. There is a general dearth of base metal coins for the years AD 81-4 with a slight rise in AD 85. However, in AD 86 and 87 there is a major peak at British sites the combined years accounting for between around 68 to 85% of all the coins. It is interesting to note that all but one of the British sites have higher totals for AD 86 than AD 87, Coventina’s Well being the exception. There is then a major fall off in supply in AD 88-9 with most sites only recording a few pieces for the period AD 90-6. However, there is a significant rise in the numbers in AD 95-6 for the PAS

and the Welsh data, largely due to an influx of sestertii. We will return to this below.

The Rhine / Danube Frontier and Italy pattern is very different from the British groups. There is much better representation in the period A 81-4 with larger rises in AD 85. There is not the

pronounced peak in AD 86-87, although Andrew Hobley has noted this for Galla Belgica (North-Eastern Gaul) and his statistics will be included in the next version of this article. There are significantly higher proportions of coins in the AD 88-94 period, before the continental groups fall below the British sites in AD 95-6.

David Walker, in his Bath report, writes extensively about this period of ‘sporadic supply’ of coinage to Britain, noting that during the later years of Agricola’s campaigns (AD 81-4), only small amounts of new silver and next to no new base metal coins were arriving in the Province (Walker 1988, 286-88). Obviously, in AD 86-7, there was a major decision to supply Britain with copious quantities of base metal coins, especially asses. However, after 87, there was only a small amount of base metal coinage arriving before the slight rise in AD 95-6, a phenomenon not noted on the Rhine / Danube Frontier nor in Italy. Overall, the supply of base metal coinage to the Rhine / Danube frontier was more consistent during Domitian’s reign.

It is interesting that previous research has not been able to pick up the increased totals for sestertii of AD 95-6 in Britain. This is where the PAS and Welsh (IARCW) provide important extra data. One has to ask why there might have been this influx of large base metal coins in AD 95-6. The answer might lie in the relatively small amount of new silver sent to the Province in AD 95-6, as shown on Table 7. Was an extra injection of sestertii required to make up for a shortfall in silver? This might be supported by the fact that all but one of these sestertii have been found in what one could term the military zone of the Province.

References and further reading:

I. A. Carradice and T. V. Buttrey, The Roman Imperial Coinage, Vol. II, Part 1 (Spink, 2007)

D. R. Walker, Roman Coins from the Sacred Spring at Bath, Part 6 of B. Cunliffe (ed.), The Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath, II: Finds from the Sacred Spring (Oxford, 1988), pp. 286-88; A. S. Hobley, An Examination of Roman Bronze Coin Distribution in the Western Empire A.D. 81-192 – British Archaeological Reports International Series 688 (1988); RIC II (part 1; 2007), pp. 261-3

P. Guest and N. Wells, Iron Age and Roman Coins from Wales (Moneta 66, 2007). This comprehensive survey of coin finds from Wales, includes coins from hoards, excavation and metal detecting.

For Coventina’s Well, see L. Allason-Jones and B. McKay, Coventina’s Well (Chesters Museum, 1985).

For Richborough, see J. P. Bushe-Fox, First to Fourth Reports on the Excavation of the Roman Fort at Richborough, (1926, 1928, 1932, 1949)

B. W. Cunliffe, Fifth Report on the Excavations at the Roman Fort at Richborough (1968)

P. Walton, Rethinking Roman Britain: Coinage and Archaeology (Moneta 137, 2012), pp. 50-52